Thesis Talks: Ilia, Davis, and Me

To Kato.

For when she wants to know.

Introduction

In 2015, National Geographic published an article written by Paul Salopek, a man who, while journeying on a multi-year, 21,000-mile walk across the world, had come to take a rest in a small Georgian village. Chargali, nestled into the Caucasus mountains, gifted him a temporary home and an interesting story. Salopek named his journal entry “Republic of Verse” and the subtitle read “In Georgia, poets – not politicians – are national heroes.”[1] This is true, but perhaps it is not a naturally created reality. Across the world, colonized populations have turned to literature as a means of rebellion and educators have turned to poetry as a channel for awakening the national consciousness.[2] Georgians are no exception. Ravaged by conquest due to their country’s advantageous positioning on the border of Europe and Asia, Georgians have had little chance to enter politics. Instead, whether it was due to censorship or disenfranchisement, national leaders emerged through poetry, a piece of art — the power of which lies in its dual ability to express political thought in both subtle and revolutionary ways.

Inspired by my own Georgian nationality, this thesis is an account of the country’s identity-formation. In order to create a thorough but contained analysis of how Georgian nationality came to existence, the following research focuses on Ilia Chavchavadze, Georgia's leading public figure and poet during the nineteenth century – a period of nationalist thought prevailing across Europe. While the majority of European countries took to the task of unifying their own people, Ilia was charged with cultivating a nationalist sentiment under an additional strain of Russian occupation. Though it may have been a daunting challenge, a similar feat had been attempted across the continent.

[1] Paul Salopek, “Republic of Verse,” National Geographic. September 4, 2015, https://www.nationalgeographic.org/projects/out-of-eden-walk/articles/2015-09-republic-of-verse/.

[2] For examples of these cases, the reader can turn to “Nationalist Poetry, Conflict, and Meta linguistic Discourse” by Yasir Suleiman, “Ormo Nationalist Poetry” by Gunther Schlee, “A Soviet Patriot and Yiddish Nationalist” by Grank Gruener, “Nationalist Poets and Barbarian Poetry” by Jonathan Skinner, and many others.

Ireland, having suffered under English oppression for centuries, had given birth to Thomas Davis, who – in turn – gave Ireland a national identity. Presently, research done on Ireland's anti-colonial nationalism abounds in academia, with a significant portion dedicated to Davis’s work.[3] In order to highlight the universal aspects of literature expressing this type of nationalist thought, the following thesis offers a comparative analysis between poems published by Ilia and Davis and the methods they employed to formulate a common identity among Georgians and the Irish, respectively.

As a land of bards, Ireland had a relationship with its poets not unlike that of Georgia’s. Folklore accounts view poetry as a gift from God, “a gift which all the learning in the world could not give to a person, a gift which lack of learning could not deprive a person of.”[4] Though it may be surprising, Ilia, himself, was well aware of a connection between the two countries. His knowledge of the Irish issue was extensive and he wrote of it on several occasions in his newspaper – “Iveria.” In 1872, he translated a Thomas Moore poem,[5] publishing it along with his own nationalist poetry in several of the Georgian journals.[6]

[3] Some of the examples include “Defining Irish Nationalist Anti-Imperialism” by Niamh Lynch, “Rethinking Irish History” by Thomas William Heyck, “Thomas Davis, “The Nation” and the Irish Language” by Jean-Christophe Penet, and “A Nation Once Again” by Guilio Giorello.

[4] Dáithi Ó Hógáin, “The Visionary Voice: A Survey of Popular Attitudes to Poetry in Irish Tradition,” Irish University Review 9, no. 1 (1979): 45.

[5] An Irish poet, singer, and songwriter.

[6] Maia Ninidze and George Rukhadze, Ilia Chavchavade: Detailed Chronology of Life and Works - New Textual-Critical Investigations (Tbilisi: Shota Rustaveli Institute of Georgian Literature, 2017), 71.

In 1886, he wrote articles addressing the plights of the Irish. Ilia educated the Georgian populace about important figures in Irish politics such as Parnell and Gladstone, spoke at length about Irish harvest failures and poverty, and even extensively documented the history and conquest of Ireland through collections of essays. Understanding the link between these two colonized nations, his work also paid particular attention to “Rebellions in Ireland” and “Ireland’s Right to Self-Governance and its Opponents.”[1]

Two of his articles on Ireland are widely cited by scholars of Ilia’s work when they discuss his brand of nationalism. In “Ireland and England,” his compassion and understanding of the Irish colonial predicament are displayed in the descriptions he uses for the Celts: “unfortunate,” “strangled,” and “miserable.” For Ilia, Irishmen are victims of “an evil act” and carriers of colonial “trauma.”[2] And though he does not mention literary figures, Ilia highlights the work done by Daniel O’Connell – the Irish politician who scouted Thomas Davis and put him in charge of creating a nationalist sentiment.

In his other work – “The Anglo-Irish Relations” – Ilia produces an interesting piece of writing. He analyzes English policies concerning Ireland and writes of two major movements: those that are striving towards a political solution and those that are arguing for change through force. Ilia sees the more peaceful movements – such as that of Gladstone – slowly failing. Although he argues that “The major ideology within Gladstone’s proposals, whether it be today or tomorrow, will ultimately be victorious because at the head of these, as we have often said, sit truth and love of mankind.” He continues, “These two cornerstones of man’s peaceful existence and happiness cannot be defeated, cannot be overshadowed, and sooner or later will find a way and will hold their rightful place within every society.”[3]

Ilia speaks further about the growing call for violence within the Fenians[4] and the Irish Americans, and fears that this can lead to England justifying brute force against the Irish. Though he also highlights his understanding of how this tactic of the revolutionaries can be used to apply significant pressure to England.[5] It must have been clear to Ilia’s readers – after the publication of such a large volume of articles on the Irish – that there was a connection between the colonial realities of Georgia and Ireland.

[1] Maia Ninidze and George Rukhadze, 218-236.

[2] Ilia Chavchadze, “Ireland and England” [in Georgian], Iveria (Tbilisi), 1886.

[3] Ilia Chavchadze, “Anglo-Irish Relations” [in Georgian], Iveria, (Tbilisi), 1886, 4.

[4] A collection of organizations dedicated to Ireland’s independence in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

[5] In a peculiar turn of events, around 1900, the “Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland” published an article on Georgian literature, paying particular attention to Ilia’s work.

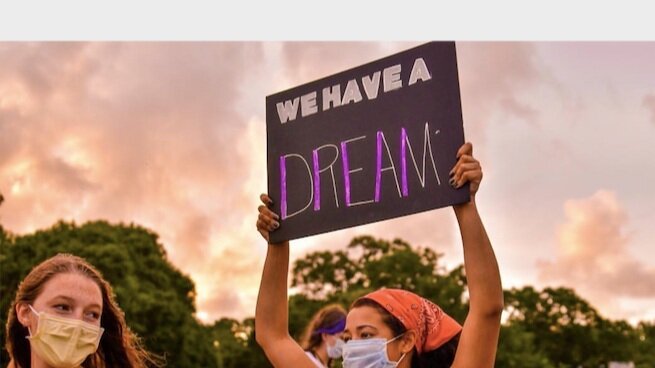

Today, Ireland continues to be an example of anti-colonial struggle, but little has been written about Georgians, their perseverance against the Russian Empire, and their guide in the fight – Ilia Chavchavadze. This nation of less than five million has kept her language, traditions, churches, and history; but while the rest of the world remains ignorant of her struggle for existence, Georgia has herself started to forget about the true nature of her nationalism. This is a nationalism of the colonized. It is a nationalism of Davis and Ilia, one that strives for inclusion, one that has a history of struggle as a bigger unifier than any ethnicity, religion, or race.

Therefore, this research attempts to show how an inclusive brand of anti-imperial nationalism was created by poets in Georgia and in Ireland in hopes that somewhere along the line, Georgia can also become a country we turn to for discussions on national identity-formation. To those Georgian-speakers who come across this text, take it as a call for action. Translate, so that our literature can be read and appreciated by the rest of the world; so that the Irish, the Indians, and the South Africans can find their own faces in Ilia’s poems. Translate, so that our own people are reminded of what we have in common with the Irish – that we have a nationalism birthed out of a history of struggle and that it is not in our nature to be oppressed or to oppress others.

The rest of this study is organized through five additional installments. Installment two will serve as an overview of academic literature already existent on the topics of nationalism, linguistic nationalism, anti-colonial nationalism and nationalism within the countries of Ireland and Georgia. The third installment will provide a short description of the research methods used in this text. A historical context section will follow along, attempting to give a summary of events which impacted the poets. This will lead to a comparative analysis of the poetry selected from Ilia and Davis’s works, and the thesis will culminate with a conclusion and several recommendations for further research surrounding this topic of nationalist verse.